Here’s my take on the PBS Monopoly doc (Ruthless: Monopoly’s Secret History) that first aired on February 20th. In general, I would say it was quite good and the best of its kind, certainly 100x better than the History Channel doc The Toys That Built America (which seemed like an infomercial for Hasbro and included numerous historical distortions and omissions, bordering on outright fabrication).

If someone is unaware of the history of the game, this would be an excellent starting point– with a few caveats.

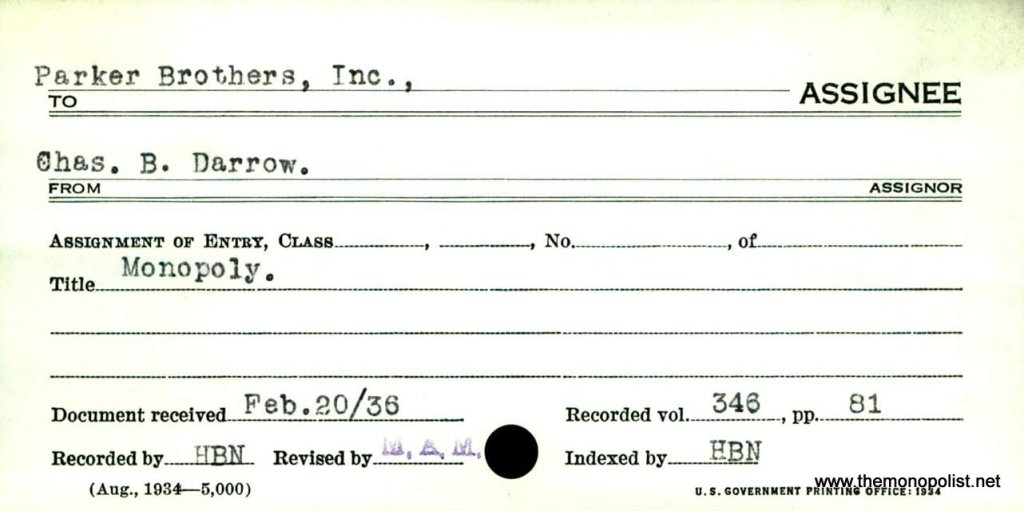

FYI there are two schools of thought regarding Monopoly history, first the corporate viewpoint as espoused first by Parker Brothers, and then Hasbro. At first this was to falsely claim that Charles Darrow was the sole inventor, but later morphed, in the face of undeniable facts to the contrary, into simply preserving the Monopoly trademark and intellectual property above all else.

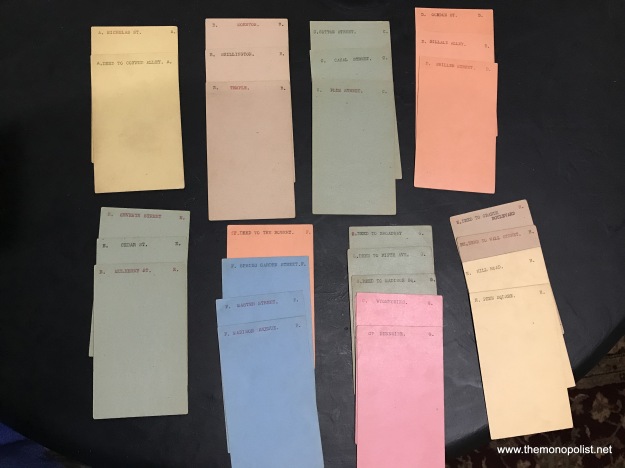

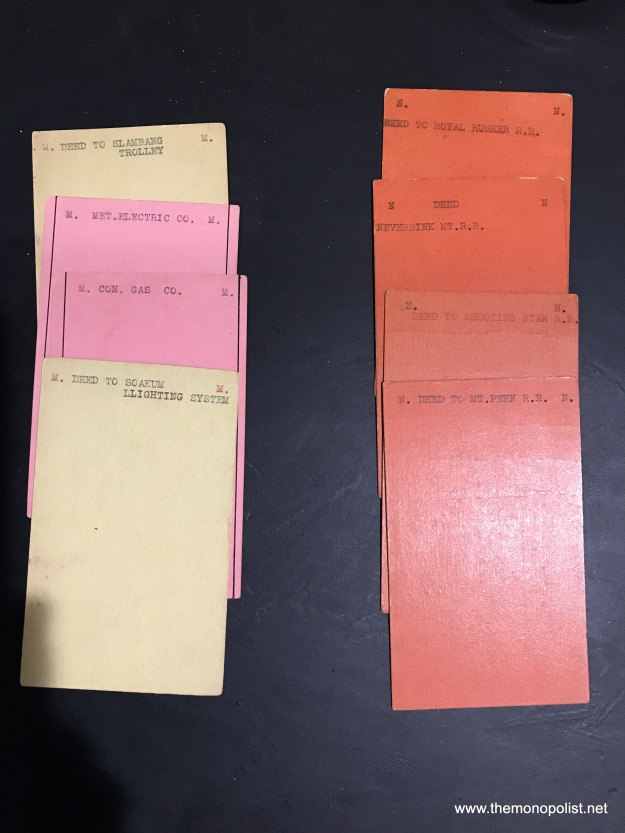

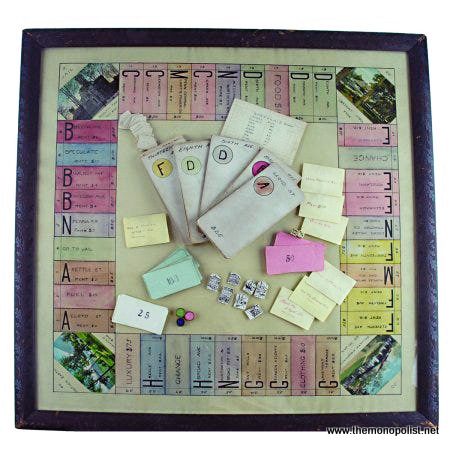

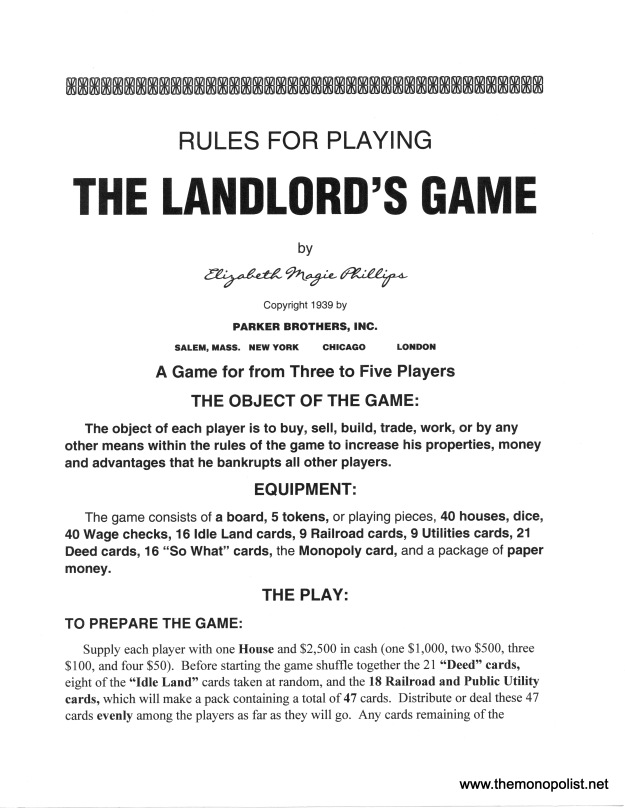

The second point of view is the revisionist one as put forth first by Dr. Ralph Anspach, who uncovered the true history of the game after he was sued by Parker Brothers over his game Anti-Monopoly. It is thanks to Anspach that we now know that Monopoly was a simplification of The Landlord’s Game, created by Elizabeth Magie (Phillips) and how it morphed over a 30-year time span in the hands of its small but growing band of devoted players.

However, IMHO Anspach later drew some conclusions that went too far in his book, which was eventually called The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle.

With Anspach in retirement (he died in 2022 in his 90s), the Swindle cudgel was taken up by journalist Mary Pilon in her book The Monopolists. She figures prominently in the PBS doc.

Phil Orbanes was also among the talking heads in the doc. A long time Parker Brothers employee, he became their de facto historian and told his corporate bosses that the true history of the game could not hurt them, because the firm (in the 1930s) had legitimately bought up all the intellectual property rights there were to be had, including Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ second Landlords Game patent.

The PBS doc goes to great lengths to give both Elizabeth Magie Phillips and Dr. Ralph Anspach their due, which is very commendable.

Unfortunately, the Swindle approach ultimately dominates the doc, whose title “Ruthless,” plays into that theme. (Just who is supposed to have been ruthless is not specified in the doc, unless it is the Monopoly players themselves in their desire to win at the other players’ expense. However, by implication, I think we are supposed to believe that Darrow and Parker Brothers were ruthless.)

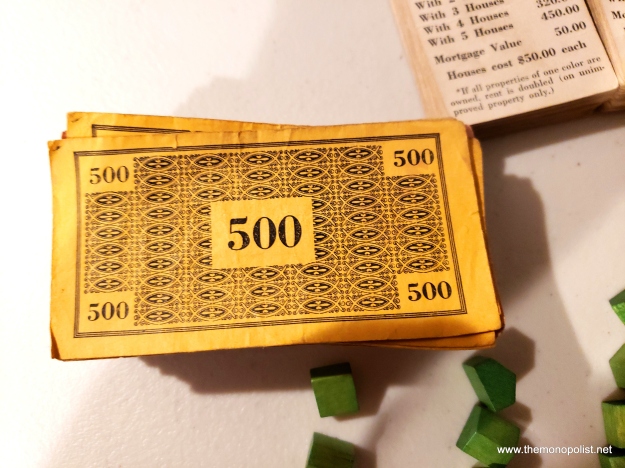

And the crux of the Swindle idea is that Parker Brothers cheated Elizabeth Magie Phillips out of millions of dollars that were rightfully hers, by paying her a mere $500 (a figure that the doc emphasizes by having several of the talking heads repeat it in a sequence of jump cuts) for her second Landlord’s Game patent in 1935. This purchase made it possible for Parker Brothers to monopolize Monopoly.

However, my research shows that rather than being a naïve person who was duped and swindled, Elizabeth Magie Phillips knew exactly what she was doing in this sale, and manipulated the situation to get exactly what she wanted. Unfortunately, the nuances of the true story do not fit easily into the historical narrative of Monopoly history that everyone apparently wants to hear nowadays, regardless of whether it is actually what happened.

Mrs. Phillips was a devoted follower of economist Henry George, and the Georgists were anti-monopolists. And what is a patent, if not a legalized monopoly? Phillips took out various patents in her lifetime, but made no attempt to enforce any of them or profit from them as legalized monopolies. Why? She was only interested in the recognition, and in receiving proper credit for her inventions.

By the time George S. Parker met with her to purchase her patent, Parker Brothers had been selling Monopoly for several months, in ever increasing quantities. She was made aware of the Monopoly patent filing by people she knew who worked in the patent office, and she knew that Parker Brothers needed the rights to her 1924 patent in order for the Monopoly patent to be approved (as an improvement).

She waited until three different firms (Parker, Milton Bradley, and Knapp Electric) had approached her before agreeing to meet with any of them, and the only firm she wanted to deal with was Parker Brothers, as she had some previous history with the firm and was an admirer of founder George S. Parker, the “King of Games.”

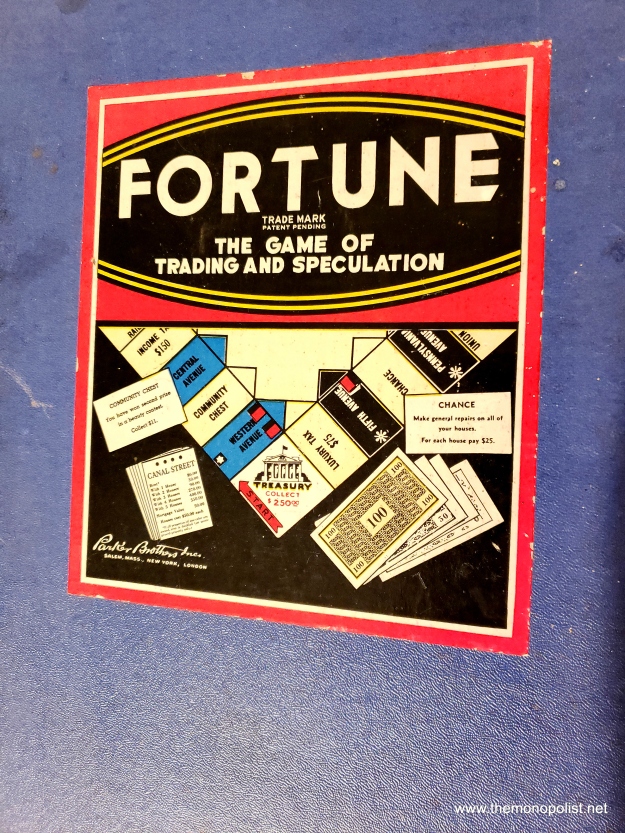

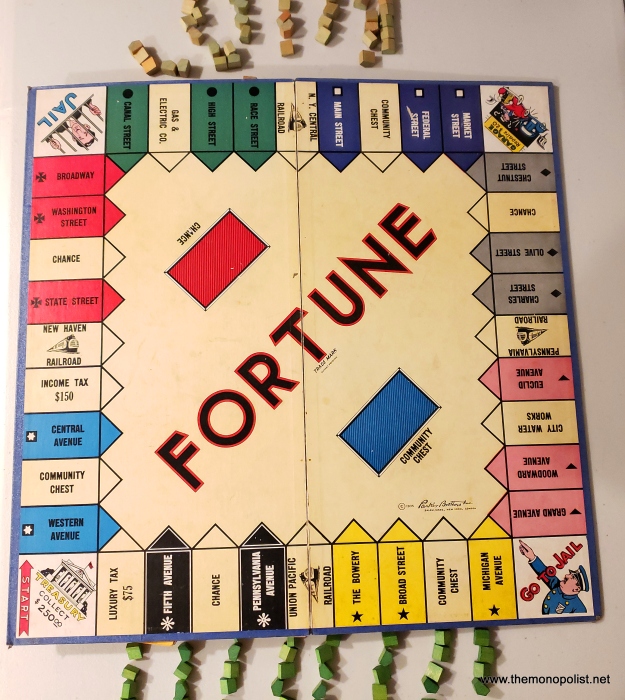

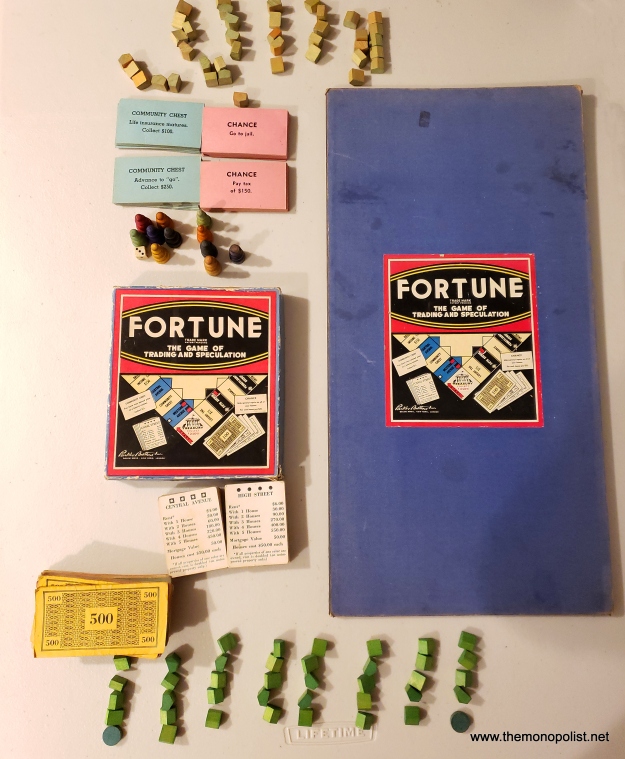

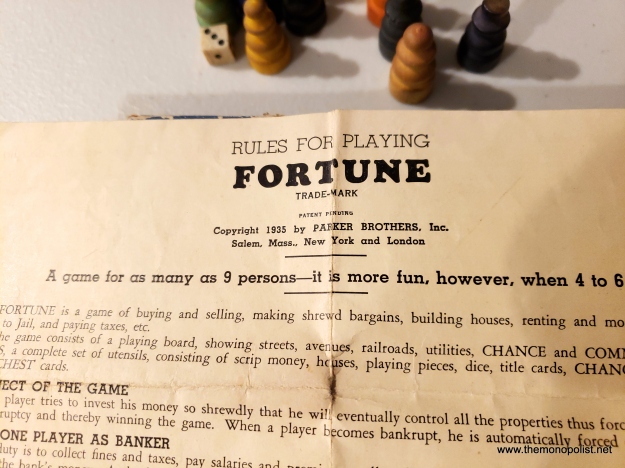

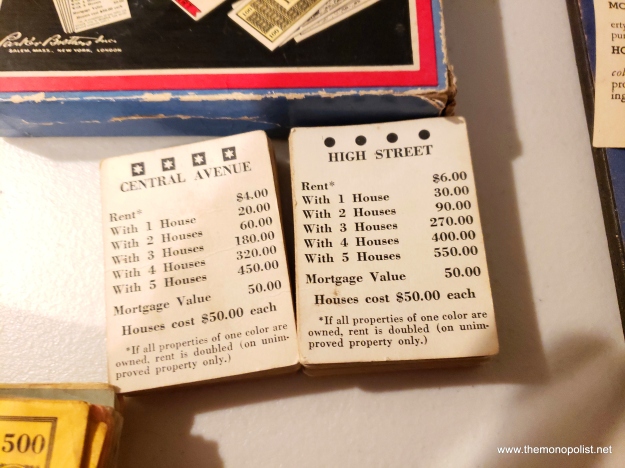

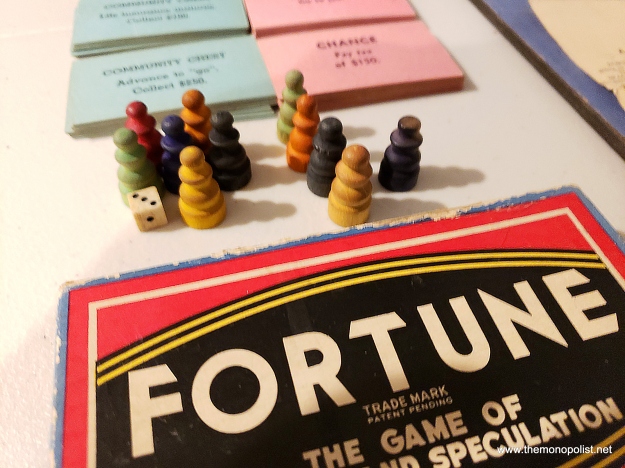

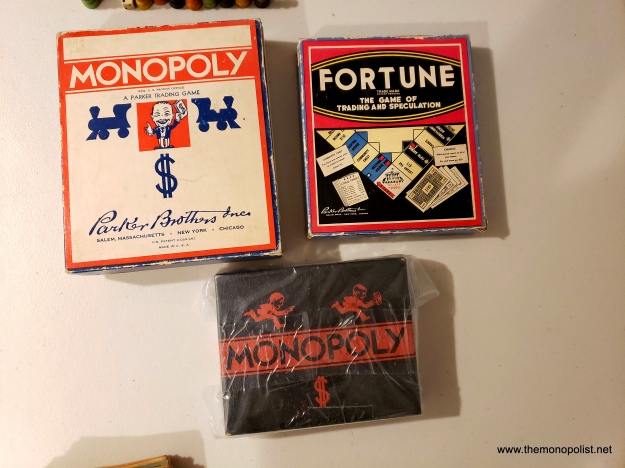

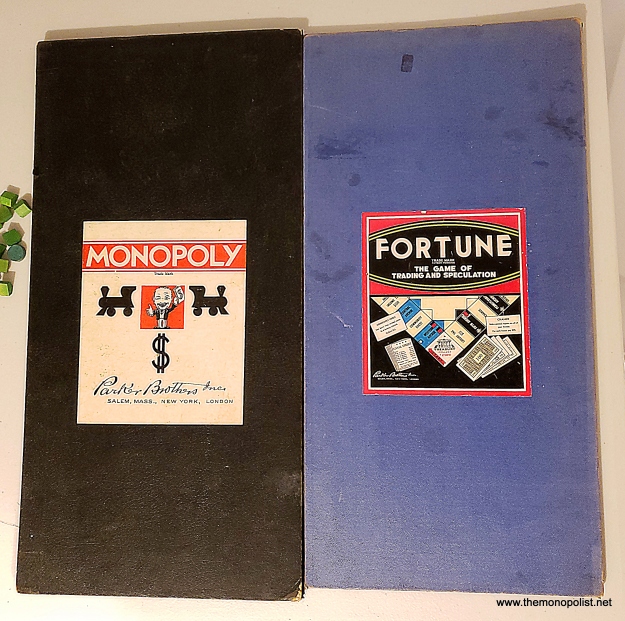

By this time, Parker Brothers was aware that Charles Darrow was not the actual inventor of Monopoly, and they were prepared to cut him out of the action if necessary. (This is abundantly made clear by their production in late 1935 of the game Fortune, which was essentially Monopoly, but without anything that Charles Darrow make any claim to having added to the game.)

Parker Brothers would have willingly given her a royalty on sales of Monopoly if she had wanted that, but apparently, she didn’t. She wanted the firm to produce her Landlord’s Game instead and only asked for a token $500 payment for her patent rights. Accepting a royalty would have gone against her Georgist beliefs and might have undermined her position in the movement, where she was quite active.

Her desire was to educate the public about the philosophy of Henry George, and not through some watered down version of her game. Besides which, she didn’t need the money– she had married a wealthy publisher, the mysterious Albert Phillips, head of the Climax Publishing Company, some of whose publications skirted the edge of the law.

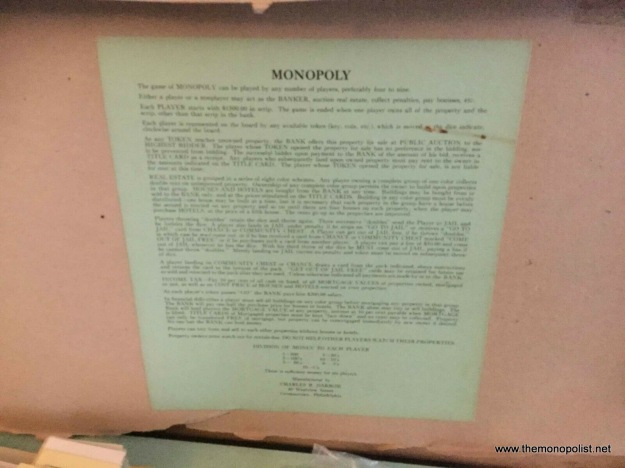

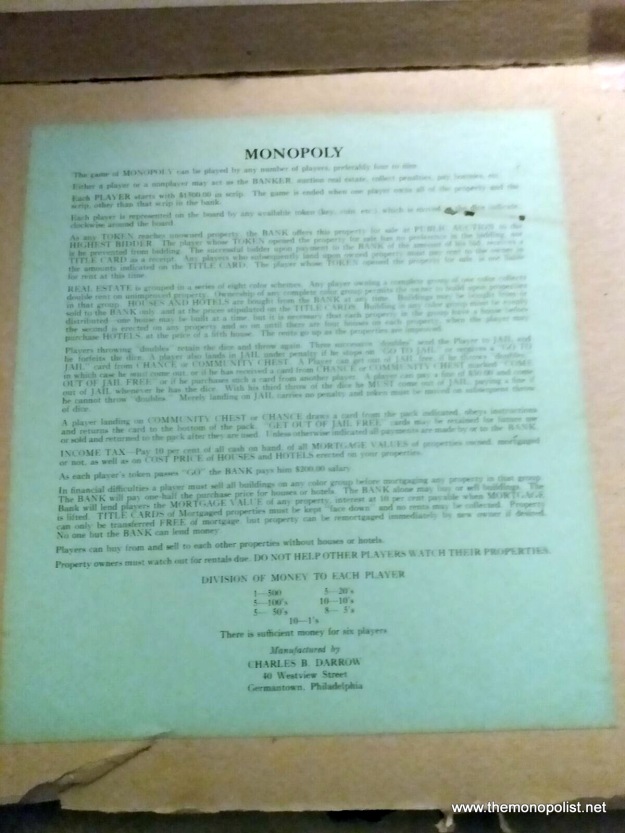

And due possibly to limitations of time, the doc does not really give Darrow enough credit for taking what was a handmade game, and transforming it with an attractive layout and handsome graphics, adding the iconic metal tokens, etc., that were so good that Parker Brothers only needed to make a few changes. Darrow was not the inventor of Monopoly, but he was certainly an important developer of the game. Elizabeth Magie Phillips invented The Landlord’s Game, and set the wheels in motion that eventually resulted, 30 years later, and with the help of the early Monopoly players, in the game we know today that first conquered America, and then the world.

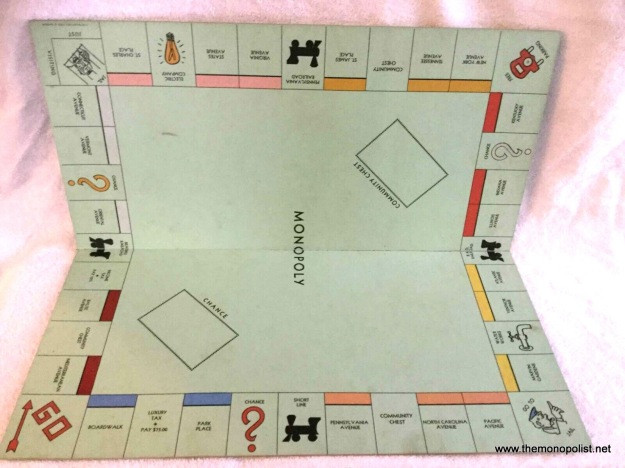

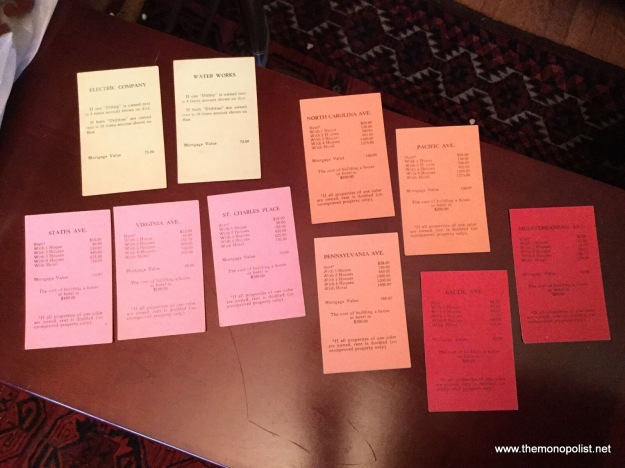

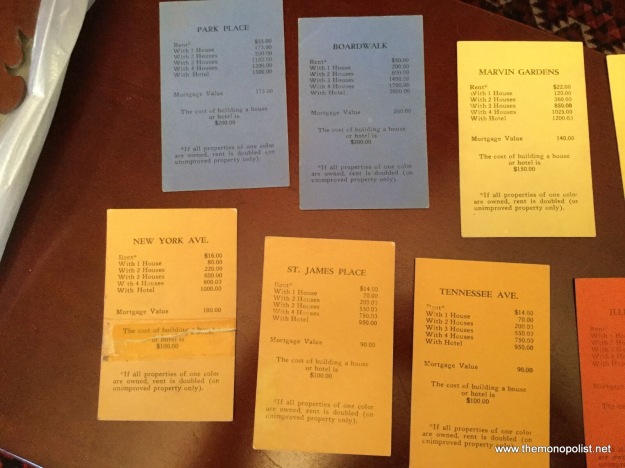

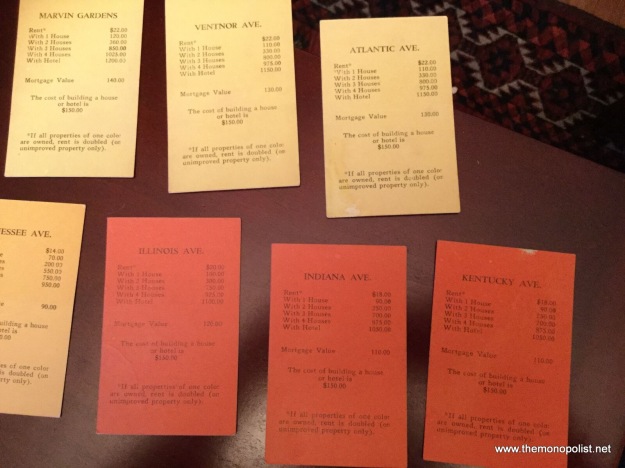

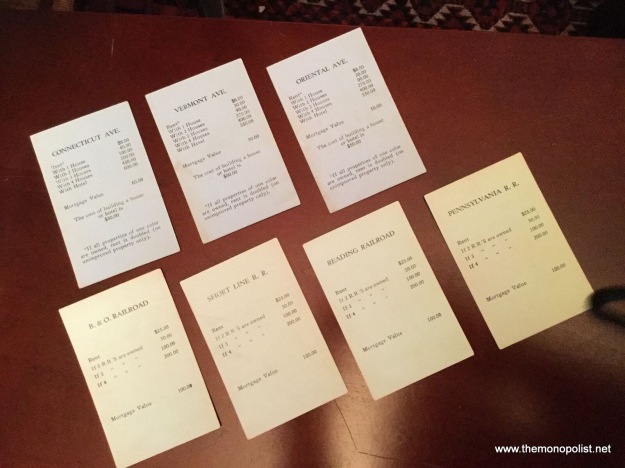

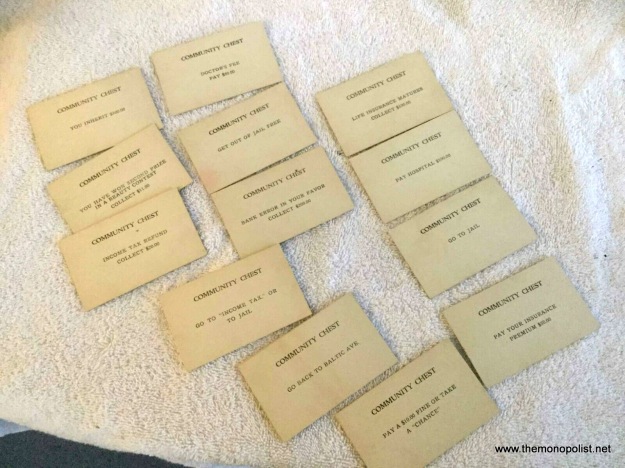

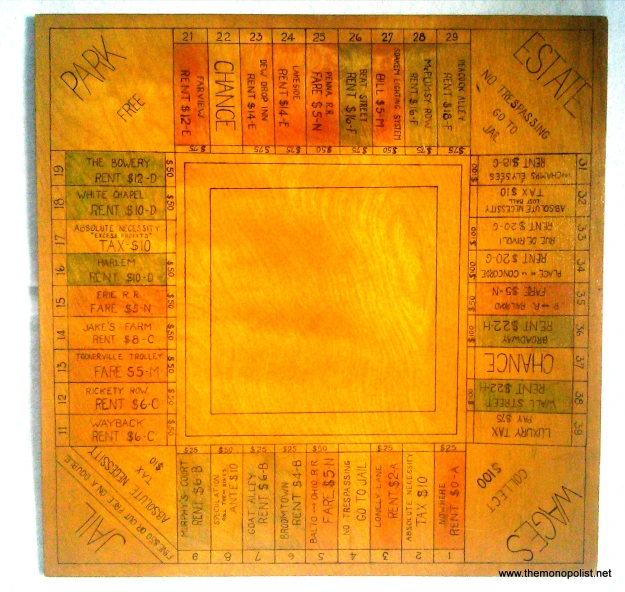

If you compare the crude handmade Monopoly board made by Charles Todd with the 1935 Darrow Black Box version (which Parker Brothers put into production with very few changes), Charles Darrow’s contribution becomes a lot more obvious.

Without Darrow’s contribution as a developer and marketer of Monopoly, it’s possible to imagine a completely different path and outcome for the game– one where a single manufacturer and version, such as Parker Brothers’, does not dominate the marketplace, but a more fractured situation resulted, as it did in the history of other “crazes,” like Tiddlywinks, Ping Pong, and Mah Jongg.

The point that the PBS documentary uses to underscore the “Swindle” idea at the end, is what Mrs. Phillips put on her 1940 census form– that she was a “maker of games,” but that her income was “zero.” But this only makes sense if you want to believe that she wanted to make money off her various games in the first place. This can be used just as easily to support my contention that she did not want to make money off her games.

At the beginning of Ruthless, the show discusses how 19th century board games were intended to be both moral and educational. Much of the success of Parker Brothers resulted from taking a different approach– that games should be fun to play. But while the documentary goes to great lengths to portray Elizabeth Magie as a modern woman, far ahead of her time, she was also a Victorian, and ultimately, she wanted her games to be moral and educational, as the Victorians did.

Stephen Ives replies:

Dear David,

Thanks for your thoughtful comments about my film Ruthless: Monopoly’s Secret History, and kudos for keeping up such an interesting website on the history of the game. Here is my response.

First, the title. Yes, it definitely refers to the way you have to play Monopoly in order to win, but it is also a reference to the strategy Parker Brothers employed to protect their best-selling game. Robert Barton practiced what can only be described as a “catch and kill” approach to games like Finance and Inflation, not to mention the folk boards he is supposed to have purchased. He was on a mission to expunge any record of The Landlord’s Game because he knew that Parker Brother’s claim to the game rested on shaky legal ground.

I take issue with your characterization that, in her deal with Parker Brothers, Lizzie Magie got “exactly what she wanted.” Magie was furious when she saw Darrow taking credit for her game and went to the press to try and set the record straight. When George Parker swooped in, in damage control mode, he was able to exploit Lizzie’s admiration for him and his company, but also her fervent desire to advance the ideas of Henry George. It is not hard to imagine Parker using this as leverage and making promises that appealed to Magie’s principles and, let’s be honest, her ego to extract the best deal possible. But $500? For the rights to what Parker knew was on track to be the best-selling board game in memory? Even if Magie’s ultimate goal wasn’t money, this to me, is the equivalent of interrogating a witness without her lawyer present. Maybe Phil Orbanes can speak to what the typical royalty offer was on a hot game that was sought by multiple companies. I am pretty sure it wasn’t zero.

And the fact that Parker Brothers issued the game Fortune tells me not that they were willing to walk away from Darrow – they had invested too much in his false narrative, and his fraudulent rags-to-riches story was a powerful selling tool in the Depression – but they were simply covering their bets in case Lizzie proved unpersuadable. Phil Orbanes and I also disagree about Easy Money, the version of Monopoly published by Milton Bradley. This game was a major threat to Parker Brothers, issued by their biggest competitor. Parker Brothers at first challenged the Milton Bradley game and then agreed to a license with Milton Bradley. Phil argues that licensing your patent to another company strengthens the legitimacy of that patent. Since Darrow’s 1935 patent was little more than a façade designed to obscure the fact that Monopoly had been in the public domain for decades, this may be true, but it seems more logical to me that Parkers Brothers knew that Milton Bradley knew Charles Darrow was a fraud, and they gave away some of their profits to keep their competition at bay.

You make a good point about a patent being, in effect, a monopoly created by the government, but patents, by definition, have a time limit, and Henry George wasn’t anti-capitalist, just opposed to the idea of entire industries and markets being controlled, indefinitely, but people like Andrew Carnegie. But the ultimate point is that even if Lizzie thought she was getting her Georgist principles validated by Parker Brothers, it is clear from their actions after signing the deal that they had no plans to honor that commitment. Granted, Lizzie’s two other games that they published may have died not because they were improperly marketed but because they weren’t good games. Nevertheless, their version of the Landlord’s Game, which they finally dropped in 1939, betrays exactly what Parker Brothers plans were. That game is intentionally designed to be totally unrecognizable from Lizzie’s original, and the company dropped Lizzie’s single tax version from the game entirely. Lizzie may have thought she was getting a good deal from Parker Brothers, but clearly, she was being exploited, both financially and in the fine print of her contract, and she was the loser on both counts.

You are right that Charles Darrow deserves substantial credit for his design improvements and for the fact that he actually got the game into places like Wannamakers and F.A.O. Schwartz. Without him, we certainly wouldn’t be playing the game we know today as Monopoly, with all of its charming and iconic design elements. And Darrow was desperate, with a son with medical issues, so it is easy to feel sympathy for his position, but in the end, he stole the idea and claimed it as his own. That has to be his ultimate epitaph.

Your final point about Lizzie is a good one. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, board games were indeed meant to be moral teaching tools. In fact, The Mansion of Happiness, which was the first board game to appear in America in 1843, was published by my great-great grandfather, William Ives, and his brother Stephen in Salem, MA. Lizzie was a transitional figure in a way. She invented Monopoly, which was the last folk game, and helped pave the way for mass-produced games whose goal was pure pleasure, but she held onto to her principles and hoped, till the end of her days, to make America a more just and equitable society. In that sense, she is a truly admirable and remarkable woman.

Thanks for your ongoing interest in Monopoly.

Best,

Stephen Ives

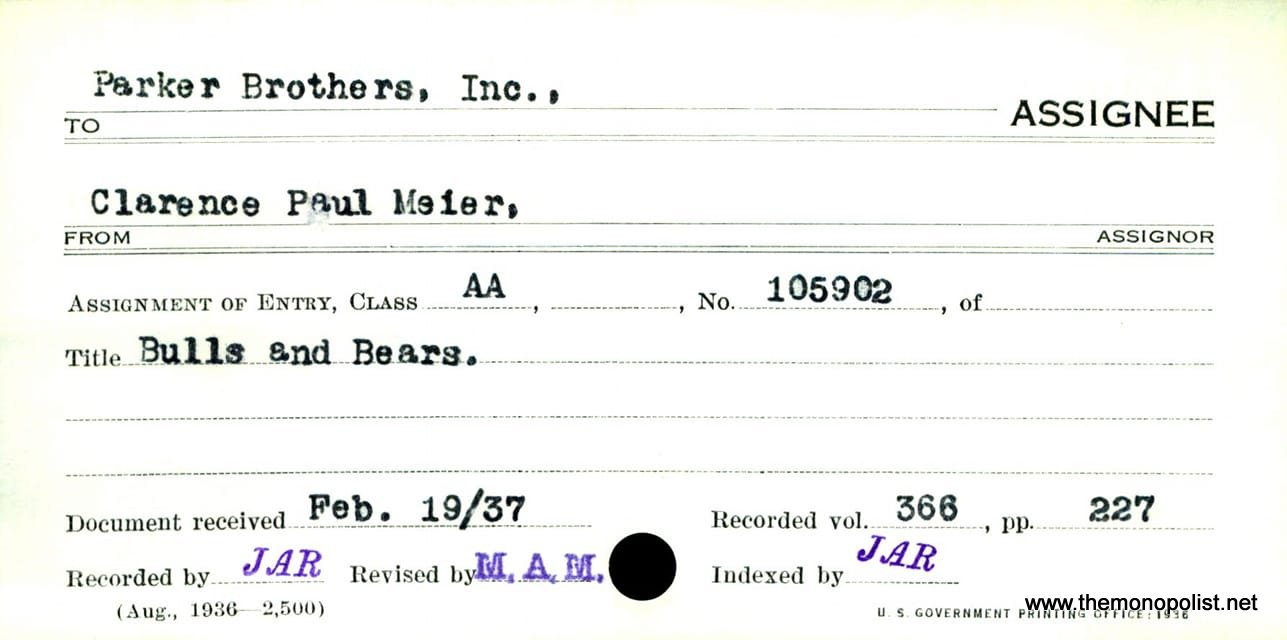

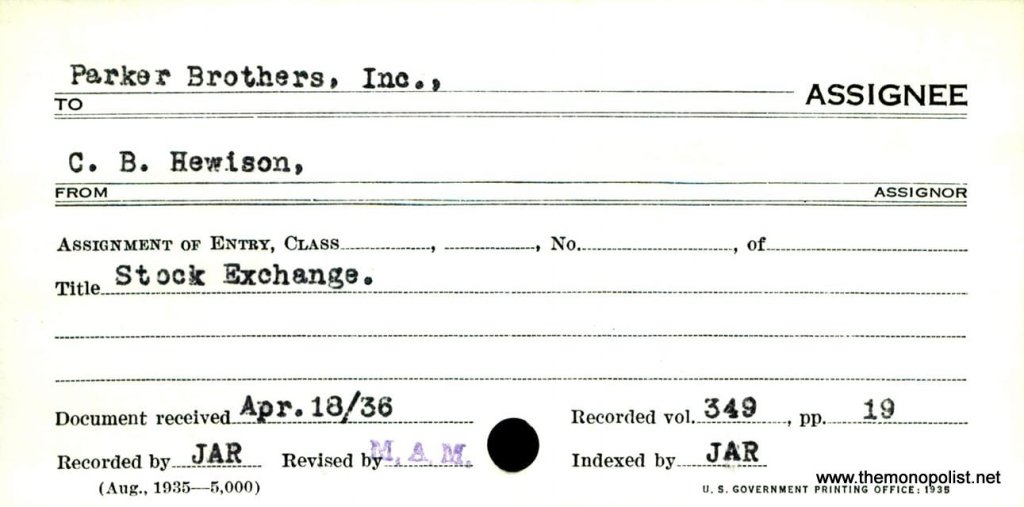

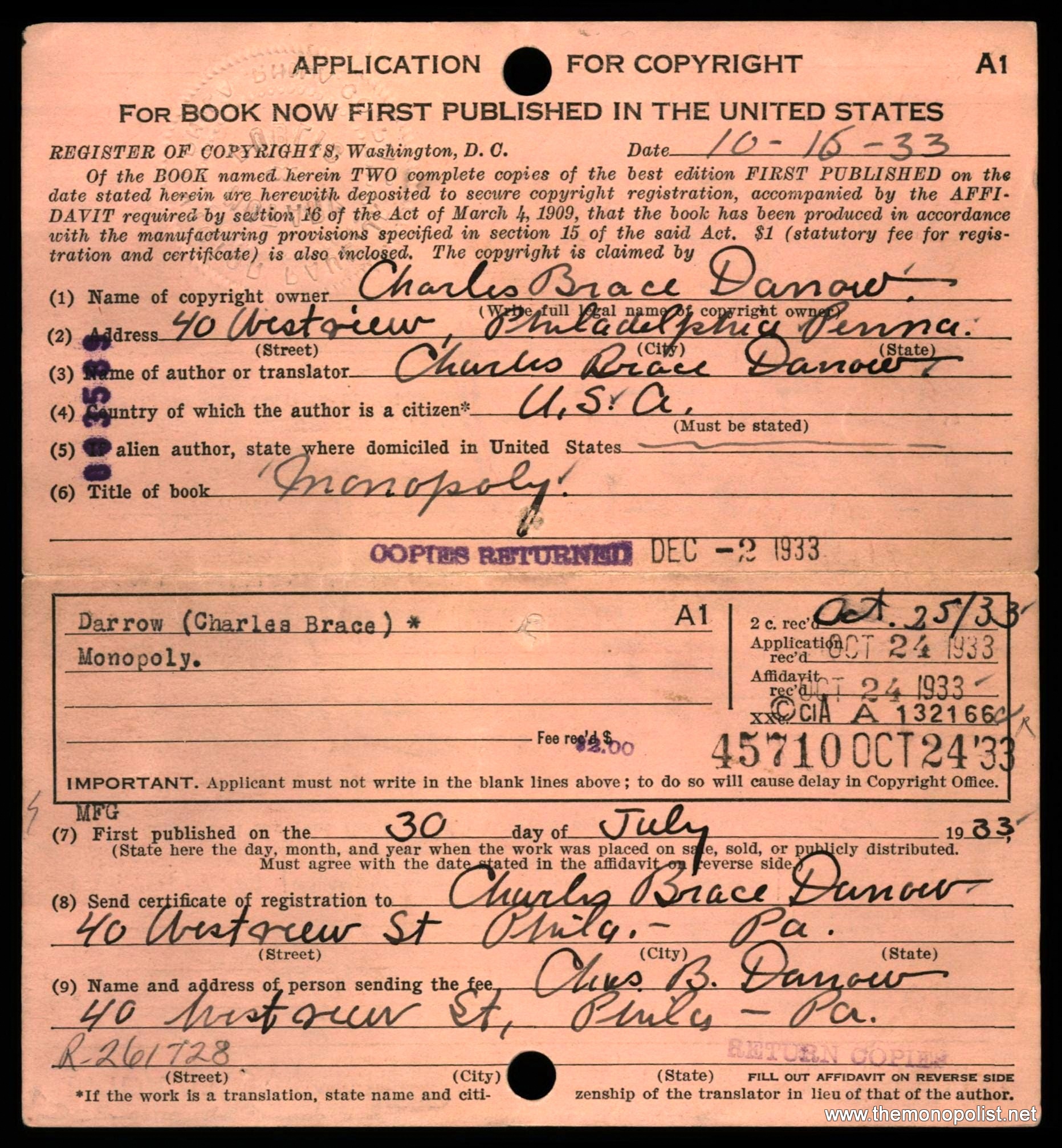

A new avenue for research into the early history of Monopoly has appeared. The Library of Congress is making images of the original index cards that go with copyright registrations available online via a

A new avenue for research into the early history of Monopoly has appeared. The Library of Congress is making images of the original index cards that go with copyright registrations available online via a